Chinese local government financing vehicles ( LGFVs ) are shifting their investment priorities from traditional infrastructure projects to digital and technology-driven infrastructure. This transition is largely driven by a slowdown in demand for conventional infrastructure and a growing need to support emerging sectors such as electric vehicles ( EVs ), smart cities, and data centres.

Over the past 15 years, China’s urbanization rate has risen significantly, from 49.95% in 2010 to 67% last year, according to data from Statista. This rapid growth has led to a saturation of demand for basic infrastructure, which historically has been the core focus of LGFVs. According to a recent report from Moody’s, the construction of roads, pipelines, and sewage systems is no longer expanding at the previous pace, reducing the need for large-scale traditional infrastructure investment.

Meanwhile, the central government continues to place strong emphasis on technological developments. In the Two Sessions in March, policymakers underscored the importance of building a modern infrastructure system that supports innovation, particularly in digital and smart technologies.

In response to these national priorities, LGFVs are increasingly being tasked by their regional and local government ( RLG ) owners to invest in “new infrastructure” that promotes digitalization and the development of high-tech industries. These investments typically include next-generation wireless networks such as 5G and 6G, artificial intelligence ( AI ) applications, EV charging infrastructure, data centres, high-speed rail systems, and smart city initiatives.

Mounting pressure

However, this strategic shift comes at a time when local governments are experiencing mounting financial pressures. The ongoing property crisis has led to a sharp drop in land sales revenue, traditionally a major source of funding for local governments. At the same time, public expenditure continues to rise.

In response, central authorities have introduced policies to contain risk, urging LGFVs to focus on projects that can generate their own cash flows and prohibiting borrowing for public investments that lack financial returns.

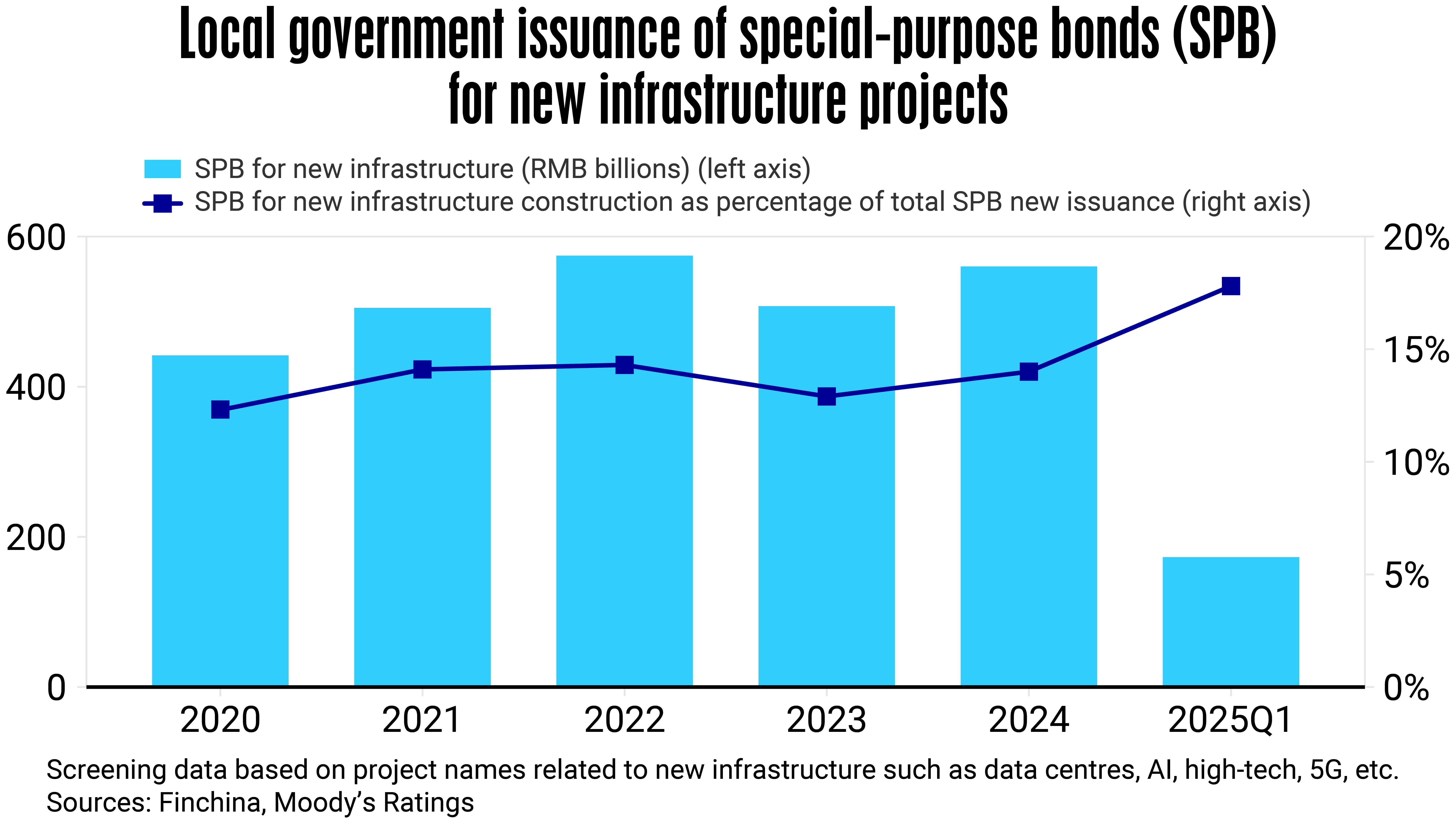

Despite these constraints, investment in new infrastructure is growing steadily. According to the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology, China’s total investment in new infrastructure under the 14th Five-Year Plan ( 2021–2025 ) is expected to reach 10.6 trillion yuan ( US$1.47 trillion ), representing around 10% of total infrastructure investment during the period.

Moody’s sees further growth in the upcoming 15th Five-Year Plan. LGFVs have issued approximately 250 billion yuan in sci-tech innovation bonds as of March 2025, with the proceeds primarily allocated to equity and fund investments in high-tech sectors.

The role of LGFVs is also evolving. Their involvement in new infrastructure now extends beyond traditional construction and public service operations. Government support mechanisms are shifting accordingly, moving away from direct repurchase agreements and towards a more diversified model that includes cash and asset injections, government bond allocations, and targeted subsidies. These changes reflect the increasingly commercial nature of new infrastructure projects.

Moreover, LGFVs are no longer acting alone in these initiatives. A wide array of stakeholders are actively participating in new infrastructure development, including central state-owned enterprises ( SOEs ), such as China’s major telecom operators and national power grid companies, as well as regional SOEs and private sector technology leaders. There are various models of participation, including direct capex investment, public-private partnerships, real estate investment trust, industrial investment, and concession-based operation.

In the western regions – Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang – LGFVs are playing a key role in accelerating economic development through new infrastructure. These less-developed areas currently account for only 21% of national GDP, much lower compared to the eastern regions.

However, they benefit from substantial fiscal transfers and abundant natural resources, including land and water, which provide favourable conditions for large-scale infrastructure deployment. Typical projects in these regions include data centre clusters, cloud computing hubs, and high-speed rail networks.

For instance, Inner Mongolia now hosts 44 data centre facilities, offering a combined capacity of 8.35 million square feet and 620 megawatts. Major providers in the region include China Telecom, with ten facilities, and China Mobile, with eight. Key clients include Alibaba, which operates significant facilities in Ulanqab A and Ulanqab B.

Financial risks

Nonetheless, financial risks associated with new infrastructure should not be overlooked. According to Moody’s, these projects tend to be more cyclical and carry higher execution and financial risks than traditional infrastructure. One of the main concerns is the risk of overestimating future demand. For example, if expected usage for data centres or EV charging stations fails to materialize, the result could be excess capacity and underutilized assets, leading to inefficiencies and potential financial losses.

In addition, the commercial nature of many new infrastructure projects also means they may not qualify for the same level of government support as traditional public infrastructure. Whereas roads and pipelines often receive strong government backing due to their essential public service functions and long-term demand, new tech-focused projects depend more heavily on market-driven cash flows. This makes them more vulnerable to fluctuations in demand and profitability. If these investments fall short of expectations, they could increase the debt burden on LGFVs and RLGs, further straining local finances.